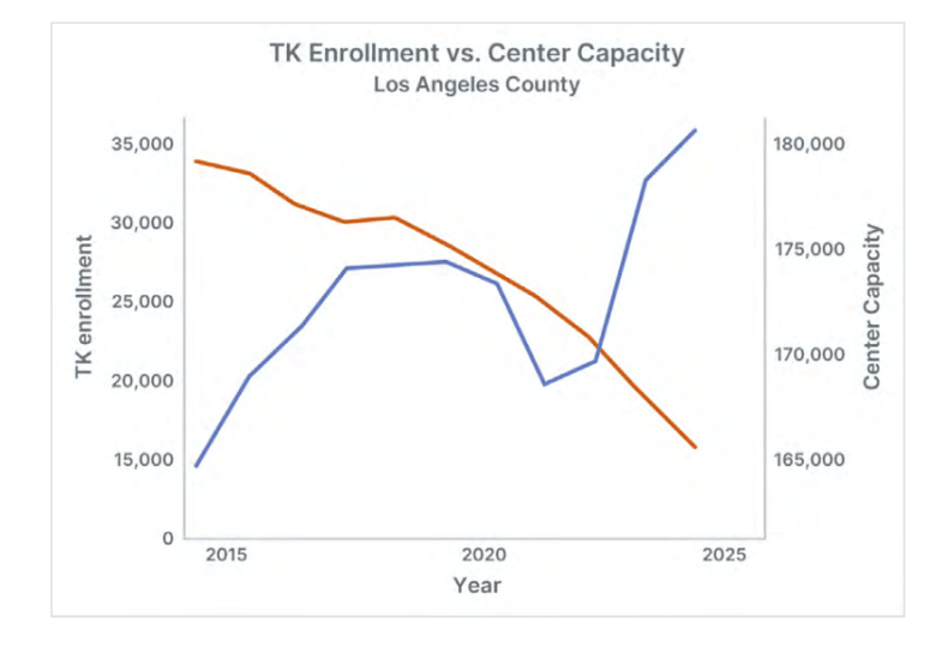

As transitional kindergarten increased, spots for 3- and 4-year-olds in public and private pre-K centers decreased

Fuller’s team also found that families in higher-income communities were the most likely to apply for the new preschool spots in public schools. In the wealthiest fifth of Los Angeles County ZIP codes, such as Brentwood, demand for public preschool skyrocketed 148 percent as families opted for a free program rather than paying up to $36,000 a year for a private preschool.

Meanwhile, enrollment increased only 50 percent in the poorest fifth of ZIP codes, where many families were left with subsidized child care centers or with relatives, especially as some public schools offered only a half-day option.

The full effect on the child care sector is still uncertain. California allowed child care centers that receive subsidies to maintain their pre-pandemic budgets even as they lost 4-year-olds. That “hold harmless” subsidy is scheduled to end in July 2026, and more closures are expected to follow.

Policymakers hoped the new public school spots would free up scarce child care spots for younger children, as 4-year-olds flocked to public schools. But there were many regulatory and financial obstacles that hindered the pivot to younger children.

“It’s not just a matter of flipping a switch to say this classroom will now serve 2-year-olds,” said Nina Buthee, executive director of EveryChild California, which advocates for publicly funded child care and early education. Operators need to reconfigure classrooms, install new sprinkler systems and hire many more teachers, Buthee explained.

“It’s a nightmare,” he said. “You have to get approval from the fire marshal and the community care licensing division of the Department of Social Services. That, in and of itself, takes six to 12 months, and that’s only if you have the money to be able to close that classroom and pay for those renovations, and then have new kids ready for when it reopens.” Many operators decided it was easier to close, he said.

More importantly, Buthee said the economics of child care centers depend on children older than 3 and 4 years old, who are cheaper to care for. State regulations require one teacher for every three or four infants or toddlers. For 4-year-olds, it is one teacher for every 12 children.

According to Buthee, most child care centers operate their children’s programs at a slight loss and make up for it with the income of their preschool children. “When you lose those preschoolers, there are no funds to compensate,” Buthee said. “The whole business model completely falls apart.”

Los Angeles officials are aware of the problems. “The expansion of transitional kindergarten in California has many benefits, as well as unintended consequences,” a spokesperson for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health’s Office for the Advancement of Early Care and Education said in an email. That office is trying to help child care and early education operators navigate the challenging market and published a new guide of financial and business resources in October 2025.

One clear lesson, according to Fuller and Buthee, is to allow community child care centers to be part of the expansion of publicly funded preschool programs rather than just public schools. That way, instead of losing children and income, these centers can keep older children and continue operating. When Oklahoma expanded its preschool program in 1998, the state also experienced widespread closures of existing centers. Oklahoma then decided to open financing to community providers. Both Fuller and Buthee praised New York City for including community centers in its preschool expansion from the beginning. Still, there were problems there too. As public subsidies for 4-year-olds increased, baby and toddler slots shrunken.

Fuller remains an advocate for early childhood education and agrees that middle-class families need relief from child care expenses, but warns that there can be detrimental consequences when well-intentioned ideas are poorly implemented.

Education systems are complicated and when a small part is changed, there can be a domino effect. Fuller doesn’t have a quick fix. Policymakers have to balance the sometimes conflicting goals of improving the education of low-income children and offering relief from the high cost of child care. There is no one-size-fits-all answer.

Contact the staff writer Jill Barshay at 212-678-3595, jillbarshay.35 on Signal, or barshay@hechingerreport.org.