In the early 2000s, when Dr. Alexandra Cvijanovich was completing her medical training in Utah, her team cared for a 13-year-old boy with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a degenerative neurological disease that can be fatal. It’s a rare complication of the measles virus that appears years after the initial infection.

The boy had been infected with measles when he was 7 months old, after contact with an unvaccinated child. Years later, he died of the complications, and Cvijanovich has never forgotten about him.

“He … got the virus before he could be immunized. And that’s just a tragic, horrible, preventable death,” she said.

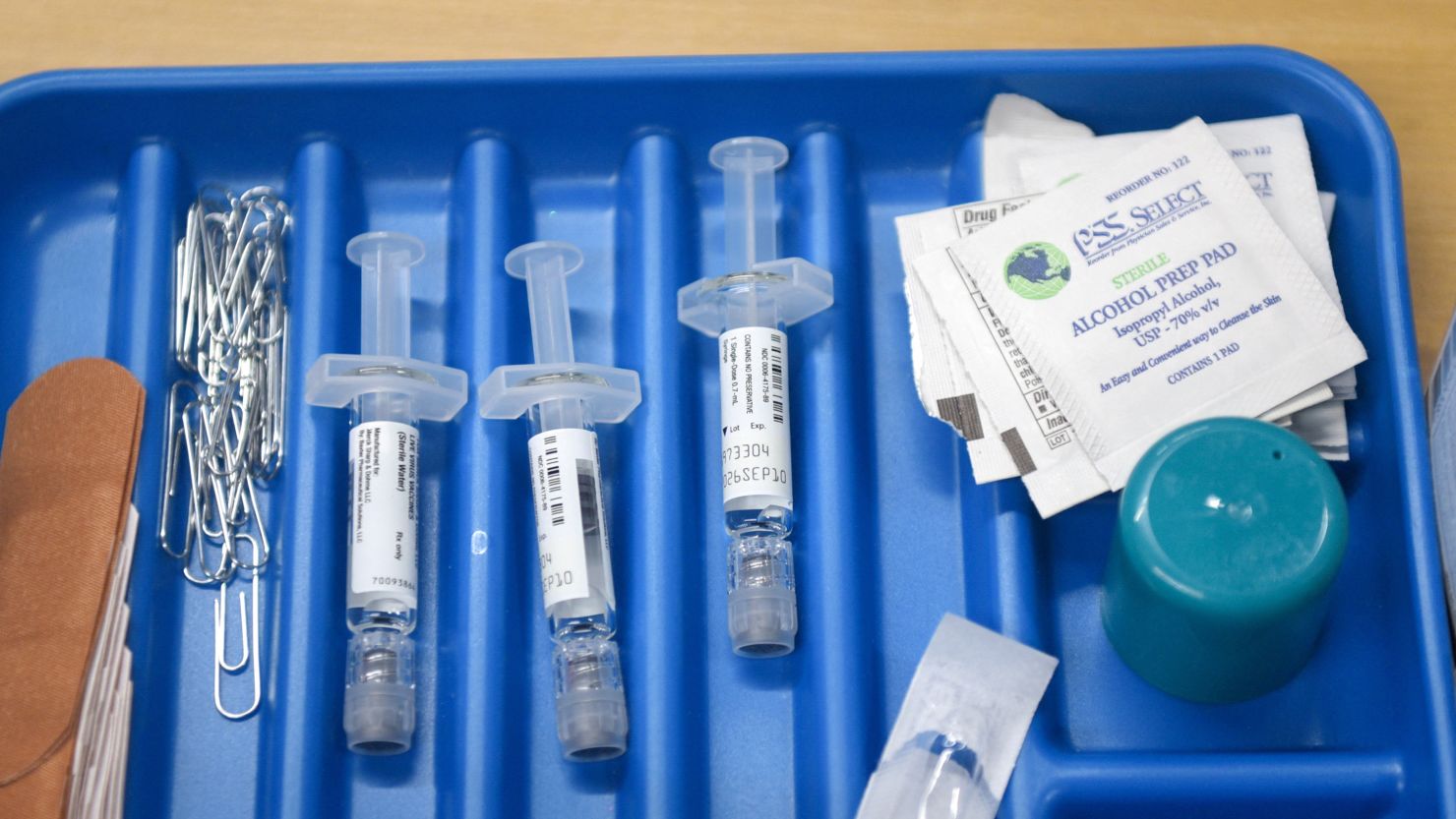

Officials recommend that children get their first dose of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine between 12 and 15 months of age. Two doses of the vaccine are 97% effective against the measles virus.

To achieve herd immunity, where enough people are vaccinated that infection doesn’t widely spread in the community, 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Now a pediatrician in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Cvijanovich treats people from all over the state – including the southeastern region, which is currently part of one of the largest measles outbreaks in decades, affecting more than 300 people across three states.

She often tells the story of her 13-year-old patient to families that are hesitant to vaccinate their children.

“I tried to use stories of patients that I’ve taken care of,” she said, “and then I also tried to plead with people that they actually think about the greater good of the community around them.”

Many pediatricians say they are seeing an increase in parents who are hesitant to vaccinate their children with the MMR vaccine and others. Here are some of their tips for communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents.