A star in a Farway galaxy is being sent to a spiral of fatality, repeatedly looting through a hot gas disk that surrounds a black hole and releasing X -ray x -ray bursts in the process. Soon, it will tear separately.

That is the evaluation of what is happening in the nucleus of a Galaxy Around 300 million light-year Called Leda 3091738, where a giant black hole nicknamed “Ansky” is being orbited by a complementary object much of low mass.

The name is derived from the official designation of the black hole of ZTF10acnsky, since its outbursts were detected by the transient Zwicky installation in the Samuel Oschin telescope at the Palomar Observatory in California in 2019.

Now, the new findings show that Ansky stands out in radiographs approximately every four and a half days, and that each Bengal lasts a day and a half before dying and wait for the cycle to begin again. Astronomers call these flares “quasi pericodic” or QPE. Until now, only eight sources of QPE have been discovered in everything UniverseAnd Ansky produces the most energetic eruptions of those eight.

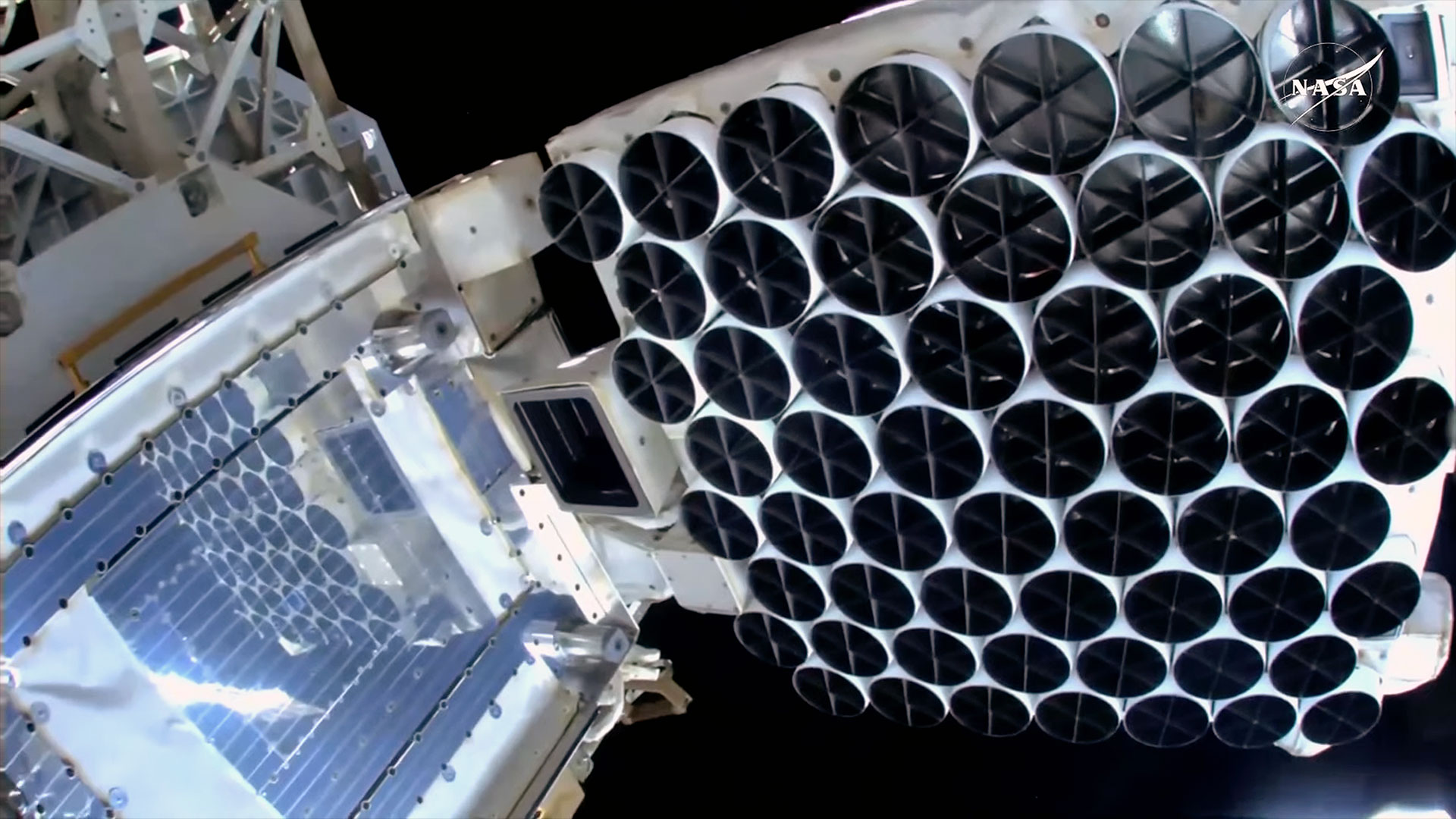

These new findings are thanks to a team led by Yoheem Chakraborty, who is a PH.D. Student of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using the Nutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) who is subject to the outside of the International Space Stationin concert with European space agencies XMM-Newton X -ray space telescope.

“These QPE are mysterious and intensely interesting phenomena,” ChakRaborTy said in a statement. “One of the most intriguing aspects is its quasi pericodic nature. We are still developing the methodologies and frames we need to understand what causes Qpe, and the unusual properties of Ansky are helping us improve those tools.”

And so, we are slowly forming an image of why Angsky produces X -ray flares.

He Supermassive black hole Involved has a mass in the order of one million Soles. It is surrounded by what is called an accretion disk, which is a hot gas bull revolving around the black holeHoping to be consumed. Meanwhile, a lower dough object, probably a rigidOrbiting very close to the black hole and is thrown periodically through the accretion disc. While it does, shock waves extend through the bull and heat the gas closest to the star’s entrance point. This gas with heating has to leave the star of the star, which makes huge clouds of expanding material in space be sent. It is the audience of this material expelled from the album that produces the QPE.

“In most QPE systems, the supermassive black hole probably destroys a star that passes, creating a small album very close to itself,” said Lorena Hernández-García of the Millennium nucleus on transverse research and technology to explore supermassive blacks. It was Hernández-García who took astronomers to discover Ansky in 2019. “In the case of Ansky, we believe that the album is much larger and can involve the objects to the party, creating the longest time scales we observe.”

The Chakraborty team monitored Ansky more pleasant 16 times a day between May and July 2024, tracing the periodicity of eruptions and monitoring any change in that periodicity. After adding XMM-Newton data to fill any void, what they discovered are bad news for the star.

The orbital energy of the star provides enough juice to heat the gas on the disc and then expel an amount of material equivalent to Jupiter Mass at speeds up to 15% of the Light speed. Every time the star crosses the album and produces a QPE, it loses some orbital energy, which makes it closure to the jaws of the black hole.

Assuming that the star has the same mass as our sunThen it would take another 400 QPE (approximately 2000 days, or 5 to 6 years, so that it loses all its orbital energy. This process shrinks its orbit, which would result in the QPE to happen more and more fast, until the star is torn separately by the gravitational tide forces of the black hole, or otherwise it merges with it. If the star has a mass greater than our sun, then it can survive for a longer time.

In any case, the degradation of the orbit of the star, corresponding to a faster QPE rate, must be the team in the coming years of girls and the rate at which the QPE are becoming more frequent should inform astronomers about the mass of the company’s star.

“We are going to continue watching Anguky for lung as we can,” said Chakrabrange. “We are still in the childhood of the understanding of QPE. It is such an exciting moment because there is much to learn.”

Nicer and XMM-Newton will monitor Ansky, who should allow a more precise prediction of when the star will run out of orbital energy and will be destroyed. When HET occurs, it will launch a large amount of torrential energy and astronomers can witness a star that is torn separately in real time, from beginning to end.

Ansky’s results were published on May 6 The Astrophysical Journal.