Europe’s next planet-hunting spacecraft has just spread its “wings” in preparation for launch.

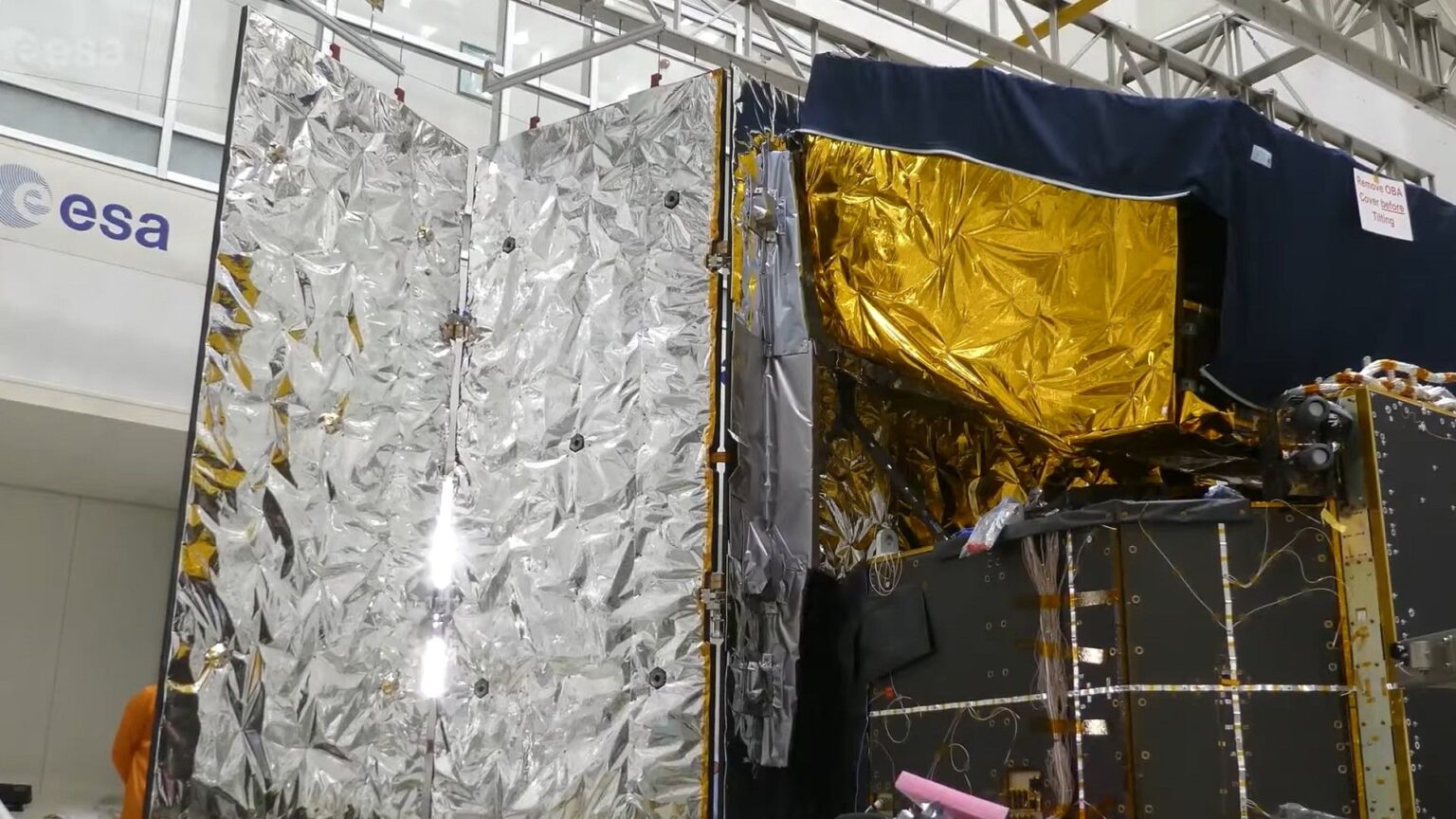

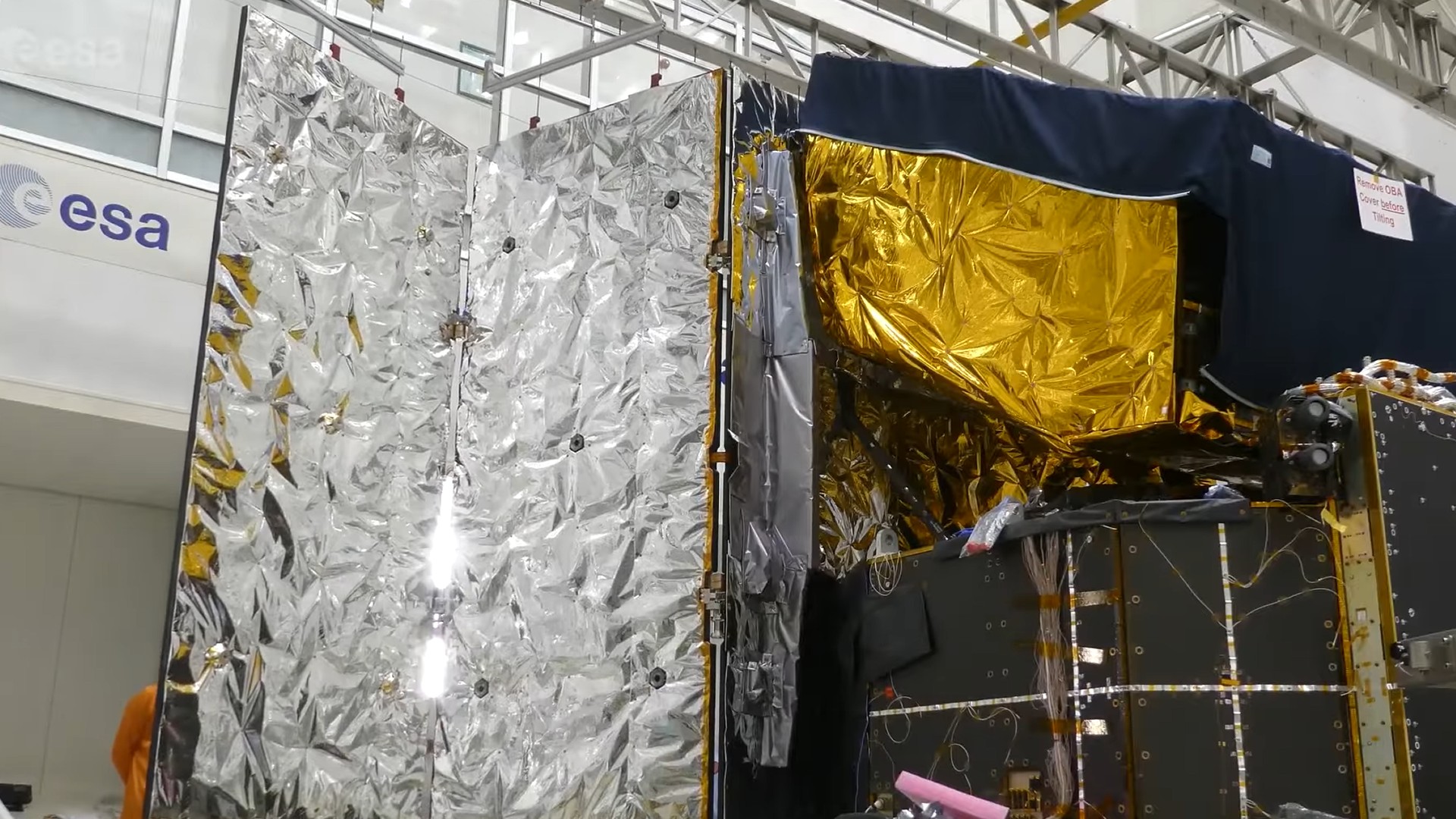

PLATOThe twin solar panels, which will power the Earth-like Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars spacecraft’s search exoplanetssuccessfully distributed during engineering testing last month in a European Space Agency (ESA) clean laboratory.

That’s a big deal, since “PLATO is on track to perform final key tests to confirm it is fit to launch,” ESA officials wrote in a statement Thursday (October 9). If all goes according to plan, PLATO will fly into space in December aboard a Arianespace Ariane 6 rocket in search of strange new worlds.

He 4 billion euro ($4.62 billion) mission is being put to the test in a clean room in the Netherlands, after engineers bolted the back of the spacecraft with a module that combines the sun shield and solar panels. As the panels collect energy to generate electricity, the sunshade will shade scientific equipment prone to overheating due to the sun’s glare.

Since the panels must fit tightly to the spacecraft during launch before being deployed in space, engineers tested the deployment of the panels in the laboratory to make sure everything was right. Like the wings, the left and right sides were carefully deployed in separate tests from September 16 to 22, respectively.

“The deployment test should be performed as if gravity were absent and the panels were weightless,” ESA officials wrote. “To do this, the panels were suspended from a support frame, with a system of pulleys that moved while the panels were gently deployed.”

Engineers then verified that the power was working using a “special lamp to simulate the effect of sunlight.” The next step is pre-launch testing: shaking and popping PLATO to simulate the rocket taking off, and then placing the spacecraft in a large chamber to simulate the vacuum of space.

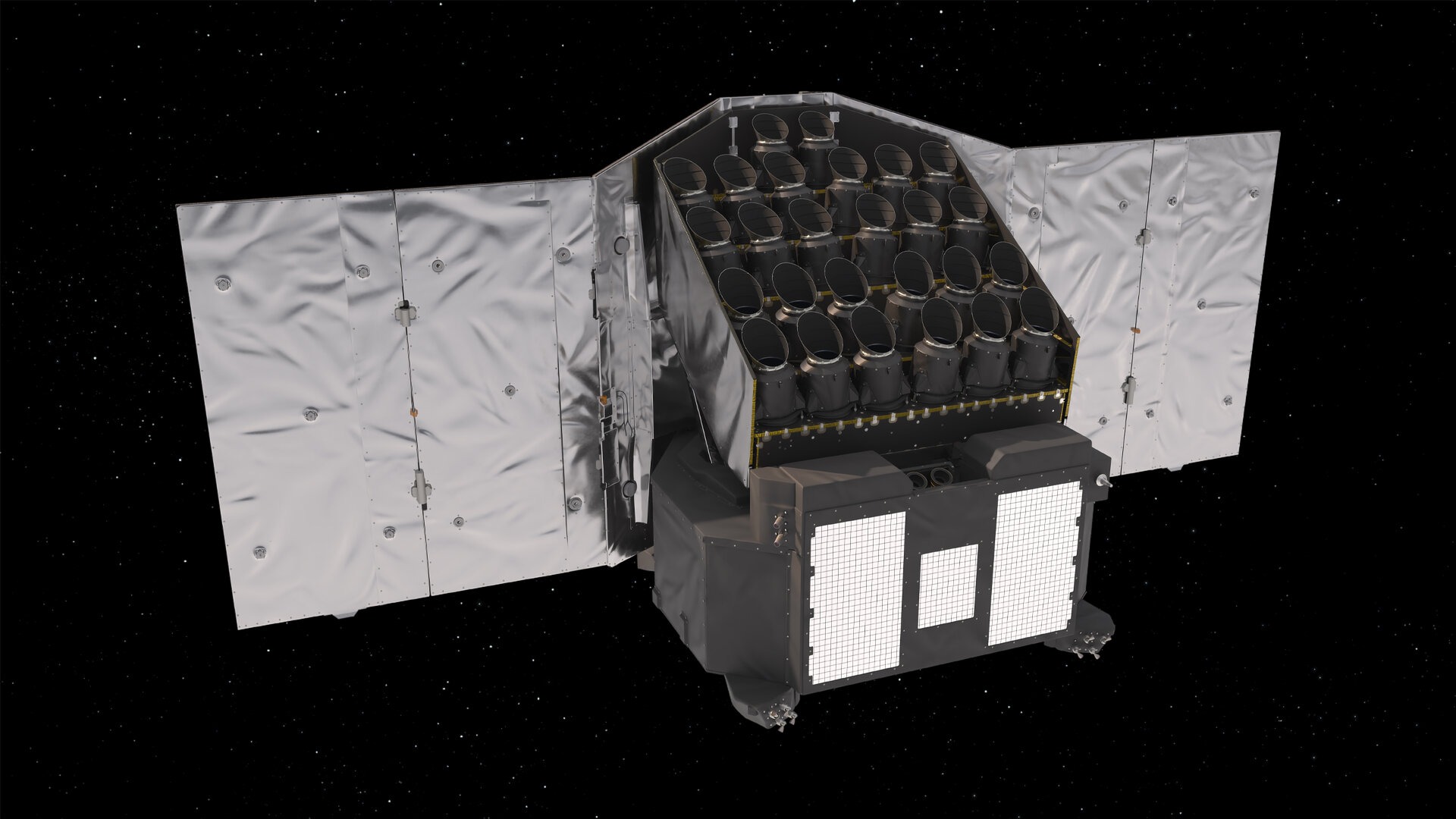

Once PLATO passes the launch and commissioning tests, comes a long search for other Earths. It will use 26 cameras to observe more than 150,000 bright chains simultaneously, looking for small changes in starlight. The goal is to capture exoplanets that slightly dim the brightness of their parent stars as the small worlds pass in front of these stars.

“To achieve the necessary high sensitivity, the cameras must be kept cool, so that each camera is kept at its optimal focusing temperature, around -80 degrees Celsius [-112 degrees Fahrenheit]” wrote ESA officials.

PLATO is expected to last at least four years according to a mission sitealthough the observatory could persist longer with funding and a well-maintained spacecraft.